Brick and Bone: How Colonial Architecture Mirrored Imperial Ambition

There's a certain melancholy that clings to old buildings, particularly those born of colonial endeavors. It's not just the weathering of stone or the peeling paint; it’s a deeper resonance, a quiet echo of ambition, displacement, and power. As an enthusiast of historical buildings, I'm not merely interested in their aesthetic beauty—though that’s undeniably important—but in the stories etched into their facades, the narratives woven into their very construction. And few eras offer a more compelling study of architectural psychology than the age of colonialism.

Colonial architecture wasn’s simply about building houses or administrative centers; it was a deliberate and powerful act of cultural projection. Think of it as a monumental "look at me," a carefully staged performance intended to intimidate, impress, and ultimately, legitimize imperial rule. The materials used, the styles adopted, and the layout of spaces all served a crucial purpose: to subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) announce, “We are here, we are superior, and this is our domain.” The psychology at play is fascinating, revealing a complex interplay of arrogance, insecurity, and a deep-seated need for validation. The desire to project power and establish dominance wasn’t limited to colonial architecture, and resonates with similar motivations seen in other historical periods and building styles, a concept explored in detail by scholars examining, for example, the extravagant displays of wealth and social stratification evident in the gilded cage of Victorian opulence.

The Echoes of Home: Transplanting Styles Across Oceans

Consider the British in India. They didn’t simply arrive and build functional structures. They built magnificent palaces and government buildings in the neo-classical style, replete with Doric and Ionic columns, pediments, and grand porticos – all painstakingly recreated thousands of miles from Greece and Rome. Why? Because these classical elements, steeped in the perceived glory of the Roman Empire, were associated with order, law, and civilization. To build in this style was to implicitly equate the British Empire with the Roman Empire, casting themselves as inheritors of its legacy.

The Portuguese, in Brazil, similarly employed Baroque architecture, its theatrical curves and exuberant ornamentation designed to project an image of power and piety. The Spanish, in what is now Mexico and the Philippines, favored a unique blend of Spanish Renaissance, Baroque, and indigenous architectural traditions. While incorporating local craftsmanship, they retained stylistic elements that reinforced their authority. The French, in Vietnam and elsewhere, favored a distinctly French style – often with an ornate, almost decadent flair. Each colonial power meticulously chose a style that resonated with its own cultural identity and its perceived position in the world order. The results were often striking, sometimes beautiful, but always freighted with the weight of imperial ambition.

Materials as Manifestations of Power

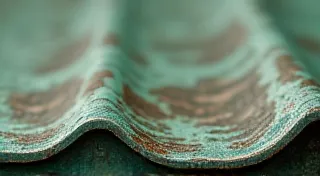

The choice of materials was just as crucial as the style itself. In many cases, colonial powers transported materials from their home countries, despite the immense logistical challenges and costs. Marble from Italy, granite from Scotland, and hardwoods from the Americas were often used in colonial buildings, signaling wealth, sophistication, and technological superiority. This wasn’t merely about aesthetics; it was about demonstrating the ability to control resources and overcome geographical obstacles. Imagine the sheer effort required to quarry stone in Scotland and ship it across the ocean to build a governor's mansion in the West Indies! The very act was a statement of power. The selection and sourcing of these materials often disrupted local economies and ecosystems, further cementing colonial dominance and reinforcing a sense of separation between colonizer and colonized.

Local materials were, of course, employed, but often in ways that reinforced the colonial narrative. Indigenous craftsmanship was utilized, but often under the direction of European architects and engineers, ensuring that the final product adhered to the desired aesthetic and served the colonial agenda. Sometimes, the use of local materials was subtly denigrated, positioning European building techniques as superior. This created a sense of cultural hierarchy, reinforcing the notion of colonial dominance. The imposition of standardized building practices often led to the suppression of traditional architectural knowledge and construction methods, contributing to a loss of cultural heritage. Even seemingly benign acts like incorporating local elements frequently served to assert colonial authority by dictating how those elements were used and integrated into the overall design.

The Layout Speaks Volumes

The spatial arrangement of colonial buildings also served a purpose. Government buildings were often designed with a clear distinction between public and private spaces, reflecting the hierarchical nature of colonial rule. Grand plazas and wide avenues were created to facilitate the movement of colonial officials and to impress upon the local population the power of the empire. Residential areas for Europeans were typically segregated from those of the local population, further reinforcing social divisions. The deliberate design of public spaces also played a crucial role in controlling movement and suppressing dissent, creating an environment of constant surveillance and control.

The positioning of buildings also conveyed a message. Colonial administrative buildings were often placed on elevated ground or overlooking indigenous settlements, symbolizing their authority and control. Churches were frequently built in prominent locations, asserting the dominance of Christianity over local religions. The visual dominance of these structures, often carefully positioned to maximize their impact, served as a constant reminder of colonial power.

The Human Cost and the Imperfect Beauty

It’s impossible to appreciate colonial architecture without acknowledging the human cost of its creation. These magnificent buildings were often constructed using forced labor, and their existence is inextricably linked to the exploitation and displacement of indigenous populations. The beauty we admire today is often built upon a foundation of injustice and suffering. The intricate details and sweeping grandeur often masked the brutal realities of their construction, where countless lives were sacrificed to create monuments to colonial power. Understanding this duality, the contrast between the perceived beauty and the inherent suffering, is essential for a complete appreciation of these structures.

As an antique accordion enthusiast, I find a parallel here. The exquisitely crafted bellows, the intricate key mechanisms, often represent dedication and artistry – but I’m always mindful of the factory conditions, the potential exploitation of workers who built them. Recognizing this complexity is crucial for a nuanced understanding of historical artifacts, architectural or otherwise. The examination of physical objects, whether buildings or musical instruments, requires a critical lens that considers not only their aesthetic qualities but also the circumstances surrounding their creation and the impact they had on the lives of those involved.

Restoration and Reflection: What Can We Learn?

Today, many colonial buildings stand as reminders of a complex and often painful past. Restoration efforts are often fraught with ethical dilemmas. Should we attempt to recreate them exactly as they were, preserving the historical record, or should we acknowledge the problematic aspects of their creation and incorporate them into the design? The challenge lies in honoring the historical significance of these structures while confronting the uncomfortable truths about their origins.

The approach to restoration should be sensitive and informed, taking into account the perspectives of indigenous communities and acknowledging the uncomfortable truths about colonial history. Perhaps the most valuable thing we can do is to use these buildings as opportunities for education and reflection, prompting conversations about colonialism, power, and the importance of cultural understanding. It's a process that demands careful consideration of whose story is being told and how, ensuring that the perspectives of marginalized communities are not erased or silenced. It’s a sentiment echoed in the study of urban planning, where the influence of water sources often revealed the deep connection between society and its environment, similar to how the river’s embrace shaped medieval urban planning.

As a collector, it’s not enough to admire the craftsmanship; I need to understand its context, its story, its legacy. It’s a responsibility we all share when engaging with historical artifacts, ensuring that we are not simply celebrating beauty but also confronting the complexities of the past.

The beauty of colonial architecture is undeniable, but it is a beauty that must be viewed through a critical lens. By understanding the psychological underpinnings of imperial design, we can gain a deeper appreciation for these buildings and a more profound understanding of the history they represent.

These structures remain, standing as silent witnesses to a chapter in human history that demands our continued scrutiny and reflection. Their brick and bone tell a story – a story of ambition, power, and the enduring legacy of colonialism. It's a legacy that often manifests in unexpected ways, echoing through time and influencing the very fabric of modern society. The subtle impact of these historical forces can be seen even in the forgotten corners of the world, where remnants of a bygone era whisper tales of lost empires and displaced cultures, much like the ghosts in the gable of vernacular architecture.

Their existence underscores the vital need to remember and learn from the past, fostering a more equitable and just future for all. And as we continue to grapple with the enduring impact of colonialism, we must remain vigilant in our efforts to deconstruct narratives of dominance and amplify the voices of those who have been historically silenced.