The Ghosts in the Gable: How Vernacular Architecture Echoes Lost Lives

We often think of grand architectural marvels – cathedrals, palaces, skyscrapers – as the definitive expressions of an era. They dominate our history books and inspire awe with their scale and ambition. But what about the buildings that *aren't* grand? The unassuming cottages, the weathered barns, the humble mills that dot the countryside, whispering secrets of lives lived long ago? These are the buildings of vernacular architecture, and within their simple forms reside profound narratives, echoes of the people who built and inhabited them.

Vernacular architecture, by definition, isn't the product of a celebrated architect's vision. It's the architecture of the people, born of necessity, ingenuity, and local materials. It reflects a community’s specific climate, available resources, and cultural traditions. Unlike the imposing structures commissioned by rulers or the wealthy, vernacular buildings were built by the people for the people—farmers, artisans, mill workers, and families striving for a life sustained by the land. And they left their fingerprints all over the place.

The Language of Layout

Consider a traditional Appalachian cabin. The placement of the hearth isn't arbitrary. It served as the heart of the home, providing warmth, light, and a central gathering place for the family. The orientation of the building itself, often facing south to maximize sunlight exposure in winter, speaks to a deep understanding of the local environment. The size and arrangement of rooms weren’t dictated by aesthetic preferences but by practical needs: a large kitchen for preserving food, a small bedroom for sleeping, a separate space for livestock if the family integrated animals into their living quarters. The very layout of these spaces subtly dictated social interactions – who spent time where, and how.

Think about the traditional longhouse found across various cultures – from Native American villages to medieval European settlements. These structures, often housing multiple families, weren’t simply dwellings; they were microcosms of social structure. The positioning of families within the longhouse, the allocation of space, even the placement of storage areas, reflected status and kinship ties. The act of building itself was a communal effort, reinforcing social bonds and passing down traditional skills from one generation to the next. The architecture *became* the social framework. Understanding how these structures reflected their time is crucial, much like understanding the motivations behind concrete dreams and the sometimes-misunderstood intentions of industrial architecture.

Craftsmanship and the Hands of the People

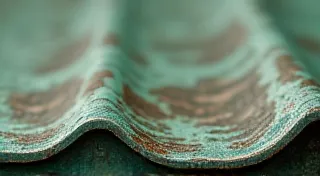

The beauty of vernacular architecture lies not in elaborate ornamentation, but in the honest expression of craftsmanship. Look closely at a timber frame barn. The way the heavy beams are joined together, the precision of the mortise and tenon joints, the skill involved in raising those massive structures—it’s a testament to the ingenuity and dedication of the builders. These weren’t merely workers; they were skilled artisans, masters of their craft, passing down techniques honed over centuries. They worked with what they had – local timber, fieldstone, clay – transforming raw materials into functional, beautiful structures.

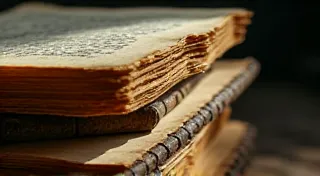

My grandfather, a carpenter by trade, used to tell me stories about the barns he helped restore. He's gone now, but I can still vividly recall the smell of sawdust and the feel of rough-hewn timber under my fingers when I’d sit at his workbench. He explained that the patterns in the wood, the slight imperfections – they weren't flaws; they were marks of the builder’s hand, evidence of a human connection to the building. Each nail hammered, each beam placed, was a conscious decision, an act of creation. He saw it not just as a job, but as a legacy. He appreciated the story behind every timber, and the legacy that each structure held, much as an archivist pores over architectural archives to uncover hidden narratives.

Whispers of Daily Life

Imagine standing inside an old mill. The rumble of the water wheel is gone, the machinery silent, but you can almost hear the clatter of gears and the shouts of the miller. The grain dust settles in the air, a faint aroma of flour lingering in the timbers. These buildings weren’t just places of work; they were hubs of community life. Farmers would bring their grain to be milled, exchanging news and gossip while they waited. The mill owner often held a position of influence within the community, acting as a lender, a mediator, and a source of essential goods.

Even the smaller details provide glimpses into daily life. A small, hidden alcove in a farmhouse might have been a hiding place for valuables or a space for quiet contemplation. A carefully carved wooden spoon found in a kitchen tells a story of a mother nurturing her family. These aren't just buildings; they's receptacles for memories, repositories of human experience. The intention behind each detail, from the most grand of structures to the smallest elements, often reflects a sense of mourning and reflection, a theme reminiscent of how the geometry of grief is manifested in memorial architecture.

Preserving the Echoes

Sadly, many vernacular buildings have fallen victim to neglect, demolition, or modernization. As we strive for efficiency and uniformity, we risk losing these invaluable links to our past. Restoration efforts are crucial, not simply to preserve the physical structures but also to safeguard the stories they hold. It's about more than just repairing a leaky roof or replacing rotting timbers; it's about understanding the original intent of the building, respecting the skills of the builders, and ensuring that future generations can connect with their heritage.

Collecting these pieces—not the buildings themselves, necessarily, but architectural salvage—can be a powerful way to connect with the past. A weathered door knob, a piece of hand-carved molding, a fragment of a painted mural – these are tangible reminders of lives lived and skills mastered. They become fragments of stories, allowing us to touch the past and appreciate the ingenuity and resilience of those who came before us. The careful restoration of a single piece of lumber can be a window into an era. These salvaged components often carry the weight of the past, acting as tangible reminders of human experience, a powerful contrast to the anonymity often associated with modern design.

A Legacy in Wood and Stone

The ghosts in the gable aren't literal apparitions, but the echoes of lives lived, hopes cherished, and skills honed. They are imprinted in the timber framing, the stone walls, the simple layouts that defined daily existence. By appreciating and preserving vernacular architecture, we’re not just saving buildings; we’re honoring the people who built them and the stories they hold—ensuring that those echoes continue to resonate for generations to come. Further understanding of these structures and the cultural contexts that shaped them reveals a shared humanity, transcending time and geography.

The preservation of such structures is not just a matter of architectural appreciation but a responsibility to the collective human narrative. It’s a recognition that even the most unassuming building can hold profound lessons about resilience, ingenuity, and the enduring power of human connection. Each weathered timber, each carefully placed stone, is a testament to the enduring spirit of those who came before us.

The cyclical nature of building and decay, creation and destruction, is a constant reminder of the fleeting nature of existence. Yet, within the echoes of vernacular architecture, we find a sense of continuity, a connection to the past that grounds us in the present and inspires us to build a more meaningful future. It's a future where we value not only the grandeur of iconic structures but also the quiet dignity of the buildings that have quietly shaped our lives for generations.

Consider the lasting impact of skilled craftsmanship. Each nail hammered, each beam placed, represents a dedication to quality and a respect for tradition. This legacy of expertise lives on in the buildings themselves, inspiring new generations of builders and artisans to embrace the beauty of hand-made structures.

In a world increasingly dominated by mass production and standardization, the preservation of vernacular architecture stands as a powerful symbol of individuality and creativity. It reminds us that true beauty lies not in uniformity but in diversity, in the unique expression of human spirit.

The reflection on structures and their purpose extends to the preservation of memory, a theme examined in detail regarding