The Cartographer’s Dream: A History of Architectural Plans

There's a quiet beauty in a blueprint, a silent story etched in lines and dimensions. It's a beauty that often goes unnoticed, overshadowed by the grandeur of the buildings they represent. But to me, and to anyone who truly appreciates the meticulous dance between imagination and execution, these plans are as compelling as the structures they birth. They’re not just documents; they're whispers from the past, glimpses into the minds of creators, and the very foundation upon which architectural dreams are realized. This is the history of architectural plans, a journey from rudimentary sketches to sophisticated digital models, and the vital role they’ve played in shaping the world around us.

Early Marks: The Dawn of Architectural Representation

Before the precision of rulers and the predictability of CAD software, architects relied on intuition and a surprising amount of guesswork. The earliest representations of buildings weren't 'plans' in the modern sense; they were more akin to elevation sketches – simplified depictions from a single viewpoint. The ancient Egyptians, for example, documented their monumental tombs and temples with surprisingly detailed drawings, though these often served more as records of construction than precise blueprints for replication. Similarly, Greek temples were likely built based on detailed models and established proportions, the techniques for which were painstakingly passed down through generations. The dedication required to achieve such accuracy speaks to a profound respect for architectural principles – a sentiment echoed in cultures across the globe, and often reflected in the unique materials and aesthetic choices.

The Romans, known for their engineering prowess, began to develop more systematic approaches. While complete, detailed plans are rare from the Roman era, evidence suggests the use of scaled models and grid systems to facilitate the construction of their vast network of roads, aqueducts, and public buildings. Imagine the sheer coordination required to build a structure like the Pantheon without the benefit of precise, replicated plans! It was a testament to their skill and organizational abilities, a process deeply interwoven with the apprenticeship system and the transmission of practical knowledge. The Romans' understanding of materials and structural integrity—often leaving behind tantalizing clues in the aging ruins—demonstrates an almost artistic understanding of architecture.

The Medieval Shift: Church Building and the Rise of Standardization

The medieval period witnessed a surge in church building, and with it, a burgeoning need for more structured methods of design and construction. Cathedrals became symbols of civic pride and expressions of profound religious devotion. While the initial designs often evolved organically, relying heavily on the master mason’s artistic vision and the collective experience of the stonemasons, a form of rudimentary planning began to emerge. These early "plans" were often drawn directly onto the quarry floor, marking out the layout and dimensions of the building. They were fluid, adaptable, and deeply ingrained in the collaborative spirit of the construction process. The emphasis on spiritual symbolism and meticulous craftsmanship during this period often resulted in structures that felt both monumental and deeply personal.

The development of guilds also played a crucial role. Master craftsmen, fiercely protective of their techniques, started to codify building methods and share standardized designs within their organizations. This contributed to a certain degree of uniformity in architectural styles, particularly in the design of churches and other public buildings. The impact of these guilds extended beyond mere construction; they fostered a unique artistic and social culture, profoundly influencing the aesthetic and spiritual landscape of the era.

The Renaissance and the Birth of the Modern Plan

The Renaissance, with its renewed interest in classical antiquity, ushered in a pivotal shift. The rediscovery of Vitruvius’s “De Architectura” provided architects with a theoretical framework for design based on geometry, proportion, and harmony. This led to a move away from purely intuitive approaches and towards more systematic planning. Filippo Brunelleschi's dome for Florence Cathedral is perhaps the most iconic example of this shift. Brunelleschi's meticulous preparation, including detailed models and complex calculations, revolutionized architectural thinking. This period's reverence for proportion and order also informed the overall design philosophy, and the influence can still be seen in numerous structures across Europe and beyond.

The invention of perspective drawing further transformed architectural representation. It allowed architects to portray buildings in a more realistic and understandable way, aiding in communication with clients and builders. This era saw the emergence of formalized architectural drawings – elevation views, sectional drawings, and increasingly, plans depicting the layout of the building from above. These plans were carefully rendered, often by skilled draughtsmen, and became crucial documents in the design and construction process. I remember once examining a set of drawings for a Venetian palazzo, incredibly detailed and annotated in elegant calligraphy. You could almost feel the architect's presence, his meticulous attention to every corner and detail. The sheer artistry involved in creating these plans, beyond the technical requirements, is a testament to the value placed on beauty and precision during the Renaissance—a period often associated with a profound understanding of how architecture shapes both the physical and spiritual environment. The way light was manipulated to achieve these effects, a theme explored in greater depth in "The Language of Light: How Romanesque Architecture Used Shadow," further emphasizes the artistic complexities of the era.

The Industrial Age: Precision, Mass Production, and the Rise of Technical Drawing

The Industrial Revolution brought about unprecedented changes in every aspect of life, and architecture was no exception. The introduction of standardized measurements, the development of precision instruments, and the rise of technical schools fueled a new level of accuracy in architectural plans. The use of ink on tracing paper became the norm, and complex mechanical drawings, detailing structural elements and building systems, became increasingly common. The rise of iron and steel construction further amplified the need for precise and detailed plans, as engineers grappled with the challenges of designing and building larger, more complex structures. This era also saw a shift in the perception of buildings – no longer solely expressions of artistic vision, but increasingly viewed as components of larger, more complex systems.

The rise of mass-produced building components also influenced architectural plans. Standardized window sizes, door dimensions, and even room layouts became increasingly common, reflecting a desire for efficiency and cost-effectiveness. While this undeniably led to a degree of architectural homogenization, it also facilitated the construction of affordable housing and infrastructure. The aesthetic choices during this period often reflected a desire for functionality and practicality, leaving behind a legacy of structures that, while not always showcasing elaborate ornamentation, possess a unique character rooted in the era's engineering advancements.

The Digital Revolution: From CAD to BIM

The advent of computers has fundamentally transformed the way architects design and represent buildings. Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software initially provided architects with digital drawing tools, enabling them to create more accurate and detailed plans. The subsequent development of Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology has taken this even further. BIM allows architects to create virtual models of buildings that contain a wealth of information about every aspect of the structure, from the location of pipes and wires to the properties of building materials. The influence of this technology is further evident in how easily we can now appreciate the profound interconnectedness of different architectural styles and construction periods.

BIM facilitates collaboration between architects, engineers, and contractors, streamlining the design and construction process and reducing errors. It's fascinating to consider how the principles of mass production, initially shaping industrial architecture, now inform the digital modeling of buildings—a point further elaborated in "The Weight of Silence: Art Deco's Unsung Sanctuary of the Common Man."

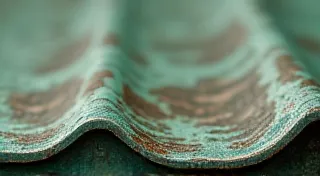

Even the aesthetic choices in architecture are closely tied to the selection and application of materials, with the character and quality of a building often shaped by the subtle interplay of decay and renewal. Exploring how the patina on aged materials contributes to the overall aesthetic and tells a story about the passage of time, as explored in The Palette of Decay: The Art of Patina in Architectural Materials, provides a richer appreciation for the enduring beauty of these structures.

Finally, the preservation of architectural archives is crucial for uncovering hidden stories and providing valuable insights into the creative processes and historical context of buildings. The importance of these archives and the narratives they hold are illuminated in The Unwritten Chapters: Architectural Archives and Their Hidden Stories, adding another layer of appreciation for the legacy of architectural design.